Data Cleaning

Proper data cleaning is essential for analytical accuracy. Raw data needs to be modified before it can be used for data analysis. These modifications are called cleaning. The cleaning process should always be reproducible, well documented, and defensive – the code should tell the user if the data isn’t as expected.

This guide outlines best practices in data cleaning, primarily concentrating on converting raw survey data to usable data for analysis of RCTs using Stata. The scope of the guide is to cover the principles of cleaning data over a project lifecycle with the goal of producing clean data in an accurate and reproducible fashion. The guide does not cover best practices in designing surveys, coding, or conducting data analysis.

In each section, we describe a set of common tasks and provide information on “what” this step is and “how” we suggest this step is completed in Stata. We also flag potential complexities. This guide assumes basic knowledge of Stata (introductory Stata training can be found here).

As part of this guide, we briefly cover other parts of the data flow, including coding best practices, deidentification, and version control. In many ways these topics are distinct from data cleaning, but all interrelate to some extent. Effective data cleaning will follow coding best practices, have a version control system, and be well documented.

Data Flow

At a high-level, the process that data goes through from when it is generated, in a survey or from an automated banking systems, is a transition from a format that reflects the structure of what is collecting the data to a structure that can be used for analyzing the information. The contents of the data do not change during this process, but the format in which they’re stored, aggregated, and labeled do.

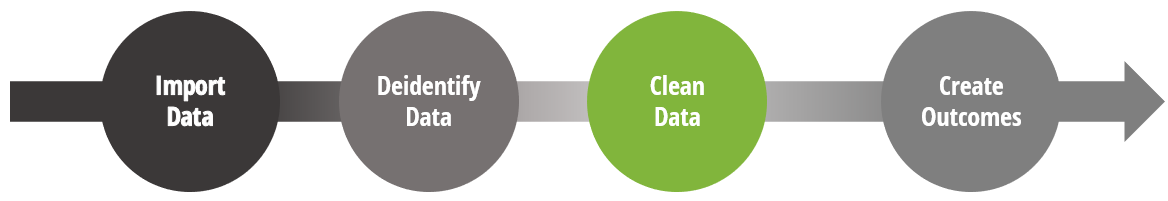

This entire process is called a data flow. At GPRL and IPA, we think of the steps in the data flow that take place in statistical software in four steps:

- Import data – all collected data is combined into a format readable by statistical software. In this step, the raw data is imported, corrections from enumerators are applied, and duplicates observations are removed.

- Deidentify data – personally identifying information (PII) is removed. This includes all individually identifying PII (geographic information, names, addresses, enumerator comments, etc.), as well as group identifying information (a combination of village and birthdate for example).

- Clean data – data content, formats, and encoding is standardized. After this, data consistency is verified and similar datasets are appended to create single datasets used to create outcomes.

- Create outcomes – individual outcome variables are created from the clean data. Data are merged and appended as part of this project to make a dataset at the level of analysis needed.

Differences in the data may make it impossible to follow this order exactly. Generally, deidentification should happen as soon as possible in the data flow if the data contains PII.

Data Cleaning

It goes without saying that raw data cannot be used for analysis. Individual survey items will not be informative on their own in most cases. Outcome variables need to be created from standardized sets of variables. In addition, documentation needs to be added so users of the data are clear on what each dataset contains.

Raw data often needs corrections and deduplication that often requires additional data from enumerators or respondents. We view data collection for replacement as part of the data collection process. Often, these replacements are collected and made as part of the monitoring process. IPA and GPRL produced many tools and resources to help this process. In particular, IPA’s data management system supports data quality monitoring, duplicate management, and corrections.

Once data is in a format to be imported, the raw data will have its own idiosyncrasies. The cleaning process attempts to standardize these idiosyncrasies in a reproducible way. Imagine you have three surveys each with slightly different outputs. Cleaning would make the output from those datasets equivalent in format, and standardized modifications made to the content. The code that produces those data should be able to be run any number of times and should tell the user if something about the data has changed so that it can’t accomplish its function.

We find it useful to think about the cleaning processing in four rough stage:

- Raw Survey Data Management

- Variable Management

- Dataset, Value, and Variable Documentation

- Data Aggregation

Each of these stages has a description in the guide, as well as a list of tasks which each has a subpage in the guide. In addition, this guide briefly touches on Stata coding practices relevant to this process, as well as some tasks related to outcome creation that require data management and are particularly prone to error in Stata.

For comments or questions, please contact researchsupport@poverty-action.org.